History

In 1831, the first church-run residential school opened in Canada. By the 1880s, the federal government created the official policy and funded residential schools across Canada. These schools were created not with the intent of educating youth but of separating Indigenous children from their families. In 1920, the Indian Act made attendance at residential school’s mandatory for Indigenous children aged 7–15 years old.

In 1920 Deputy Minister of Indian Affairs Duncan Campbell Scott outlined the goals of that policy when he told a parliamentary committee, “Our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic.”

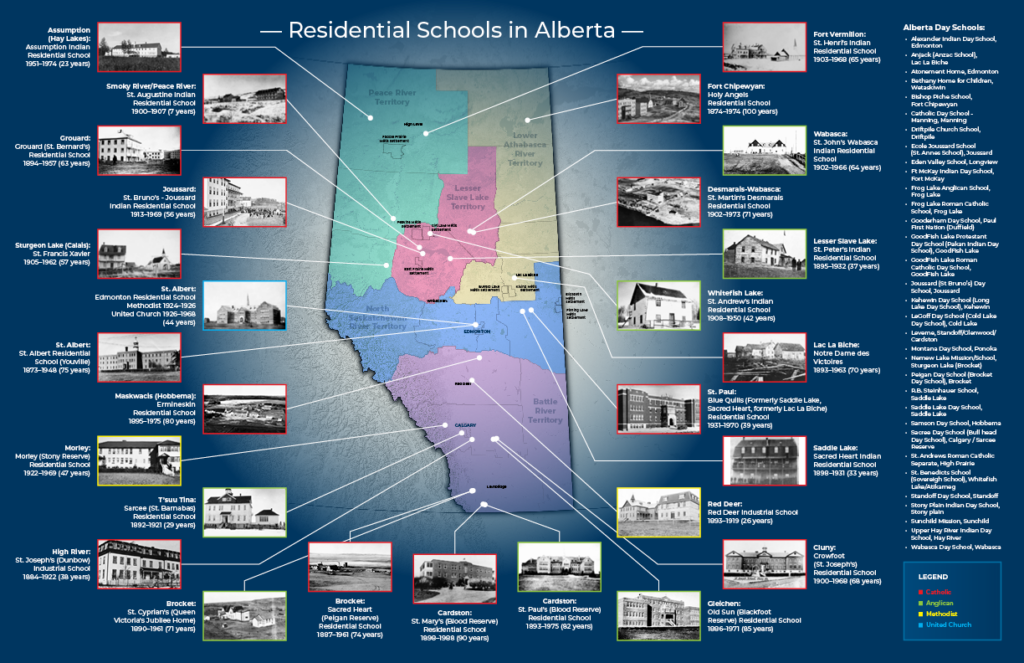

The primary goal of these schools was to assimilate Indigenous children, so they were no longer a distinct people. This goal is synonymous with cultural genocide and lasted over 150 years within Canada. There were 25 registered residential schools within Alberta, and it is still unknown the exact number of children who attended these schools since accurate records were not kept. This also makes it hard to know how many children died while attending the schools.

A common misconception about the residential school system is only First Nations and Inuit children were taken, however many Métis children also attended schools. Métis attendees are largely considered to be the “forgotten people” due to this misconception. School records often mislabelled Métis children as First Nations and moved them to First Nations and Inuit schools to maintain government funding.

Children who attended residential schools often experienced physical, emotional, and sexual abuse at the hands of church leaders who ran the schools. The schools were also full of diseases and illnesses like tuberculosis, smallpox, and influenza. Between the abuse and illness, many students died at the schools. Not every child received a grave and not every family heard their child had passed.

The last residential school in Canada was the Gordon Residential School in Punnichy, Saskatchewan and it closed in 1996.

Reconciliation and the Métis Nation within Alberta

In an effort to further our Nation on the road to reconciliation, we have created a safe space for Citizens to talk or learn more about residential and day schools. We have travelled throughout Alberta, speaking with Métis Survivors, and documenting their stories to build a list recognizing all Métis Survivors and ensure the voices of Survivors and their families are heard. In addition to interviewing Survivors, we are also researching historical data, records, and documents to educate our community and non-Indigenous communities about the cultural genocide that took place.

Truth and Reconciliation Advisory Board

In the spirit of reconciliation, we have appointed a Truth and Reconciliation Advisory Board comprised of Residential School Survivors and family members who have experienced intergenerational trauma due to the Residential School System. These board members will guide us on our journey to healing the past.

Supports & Programs

Past Events

Read about previous Truth & Reconciliation events:

Letters to the Pope

In 2022, a group of Residential School Survivors and Indigenous leaders journeyed to Vatican City in Italy to meet with Pope Francis. This group included Métis Survivor and Elder Angie Crerar, former Region 4 Vice-President Gary Gagnon, Past President Audrey Poitras, and former Métis National Council President Cassidy Caron, along with other Métis representatives. In addition to the in-person accounts from Survivors who went to Rome, the Pope was given letters written by Métis Survivors and their families. These letters served as further evidence of the long-standing trauma experienced by Survivors.